Rebuilding confidence after emotional abuse

Your sense of self is deeply tied to your memory – here’s how

Shane Rogers, Edith Cowan University

You might say you have a “bad memory” because you don’t remember what cake you had at your last birthday party or the plot of a movie you watched last month. On the other hand, you might precisely recall the surface temperature of the Sun any time when asked.

So, is your memory bad, or just fine? Memory is at the very heart of who we are, but it’s surprisingly complex once we start looking at how it all fits together.

In fact, there’s more than one type of memory, and this determines how we recall certain facts about the world and ourselves.

How do we classify memory?

Cognitive psychologists distinguish between declarative memory and non-declarative memory. Non-declarative memories are expressed without conscious recollection, such as skills and habits like typing on a keyboard or riding a bike.

But memories you’re consciously aware of are declarative – you know your name, you know what year it is, and you know there is mustard in the fridge because you put it there.

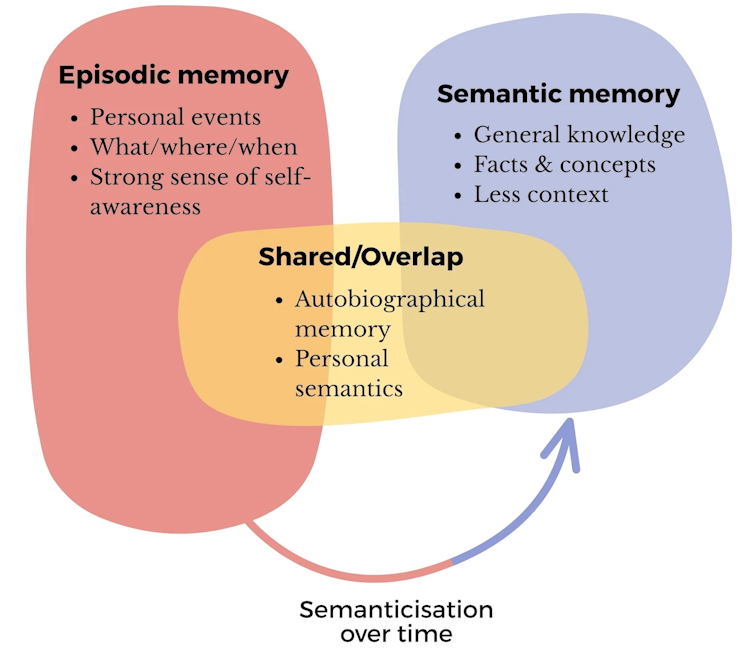

However, not all of our memories are stored in the same way, nor in the same place in our brains. Declarative memory can be further broken down into semantic memory and episodic memory.

Semantic memory refers to general knowledge about the world. For example, knowing that cats are mammals.

Episodic memory refers to episodes of your life, typically with elements of “what”, “where” and “when”. For example, I remember cuddling my pet cat (what) in my home office (where) just before sitting down to write this article (when).

A sense of self-awareness is strongly involved in episodic memory. It’s the feeling of personally remembering.

For semantic memories, this sense is not as strong – you can have detached knowledge without the context of “how” and “when”. For instance, I know that Canberra is the capital city of Australia (semantic memory), yet I can’t remember specifically when and where I learnt this (episodic memory).

Lessons from amnesia

In the mid-20th century, famous case studies of amnesic patients were the early evidence of this distinction between semantic and episodic memory.

For example, Henry Molaison and Kent Cochrane both experienced brain damage that severely impacted their episodic memory abilities.

They couldn’t recall events from their lives, but knew many things about the world in general. In effect, their personal past had vanished, even though their general knowledge remained intact.

In one interview after the accident that caused his brain damage, Cochrane was able to describe how to change a flat tire in perfect detail – despite not remembering having ever done this task.

There have also been reports of cases of people whose ability to recall semantic memories is largely impaired, while their episodic memory abilities seem mostly fine. This is known as semantic dementia.

Your age affects how your memory works

Young children have both memory systems, but they develop at different rates. The capacity to form strong semantic memories comes first, while episodic memory takes longer.

In fact, true episodic memory ability may not fully develop until around the age of three or four years. This helps explain why you have scant memories of your earliest childhood. We gain greater self-awareness around the same age too.

While episodic memory ability develops more slowly in early life, it also declines more quickly in old age. On average, older adults tend to remember fewer episodic details compared to younger adults in memory recall assessments.

In older adults with more severe cognitive decline, such as dementia, the ability to recall episodic memories is typically much more affected, compared to semantic memories. For example, they might have difficulty remembering they had pasta for lunch the day before (episodic memory), while still having perfect knowledge of what pasta is (semantic memory).

Ultimately, it all works together

Brain imaging studies have actually revealed that overlapping areas of the brain are active when recalling both semantic and episodic types of memories. In a neurological sense, these two types of memory appear to have more similarities than differences.

In fact, some have suggested episodic and semantic memory might be better thought of as a continuum rather than as completely distinct memory systems. These days, researchers acknowledge memory recall in everyday life involves tight interaction between both types.

A major example of how you need both types to work together is autobiographical memory, also called personal semantics. This refers to personally relevant information about yourself.

Let’s say you call yourself “a good swimmer”. At first glance, this may appear to be a semantic memory – a fact without the how, why, or when. However, recall of such a personally relevant fact will likely also produce related recall of episodic experiences when you’ve been swimming.

All this is related to something known as semanticisation – the gradual transformation of episodic memories into semantic memories. As you can imagine, it challenges the distinction between semantic and episodic memory.

Ultimately, how we remember shapes how we understand ourselves. Episodic memory allows us to mentally return to experiences that feel personally lived, while semantic memory provides the stable knowledge that binds those experiences into a coherent life story.

Over time, the boundary between the two softens as specific events are condensed into broader beliefs about who we are, what we value, and what we can do. Memory is not simply a storehouse of the past. It’s an active system that continually reshapes our sense of identity.![]()

Shane Rogers, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.