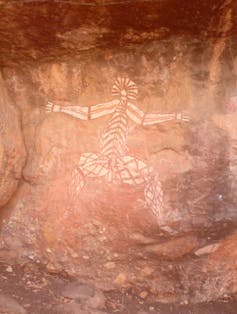

Some Indigenous paintings have lasted thousands of years … so what is it about the pigments that make them so long-lasting? Carolien Coenen/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Andrew Thorn, International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property

Some Indigenous paintings have lasted thousands of years … so what is it about the pigments that make them so long-lasting? Carolien Coenen/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Andrew Thorn, International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural PropertyIndigenous Australian practices, honed over thousands of years, weave science with storytelling. In this Indigenous science series, we look at different aspects of First Australians’ traditional life and uncover the knowledge behind them. Here we examine the chemistry and techniques behind perhaps the most iconic element of Indigenous life: rock art.

Visitors to Uluru might also find themselves at Mutitjulu Waterhole in the company of a travel guide filled with wisdom about the meaning of the paintings. Uluru has almost 100 painted sites, of which I have studied most, and tourists will encounter a dozen or less.

Anangu people will explain that the paintings have many meanings depending on the audience. An undulose band may be a snake in one story, a creek in another. A tourist may or may not be told that the paintings at Uluru are in themselves not necessarily highly charged with spiritual values but rather an auxiliary expression in response to the power of the rock itself. The main stories, the big stories, are told in the rock.

So why did people paint? What did it mean? How was it done? Why did they use certain pigments? Why has it lasted so long? The answers inevitably vary depending on where you are standing and with whom.

Painting techniques

Paint has been applied to rocks, almost all types, by a variety of application techniques. Marks were made using what appears to be a dry crayon or pastel application, where a piece of pigment-rich soft rock has been drawn across the surface.

A wide variety of implements were used as brushes to apply water-dispersed pigment, and there is ethnographic evidence of chewed bark and other suitable implements being used – as they still are today for bark paintings.

Fingers may have been used and in one rare and precious place across the flood plain from Ubirr in Kakadu, senior elder of Kakadu, Bill Neidjie, once pointed to a place in the ceiling where his footprints still remained from his youth where he was dipped in paint and pressed against the ceiling.

Stencil techniques have been used to portray everything from full bodies (the finest examples in Carnarvon Gorge in Queensland), to hands, weapons, and introduced objects of fascination such as clay pipes and wool shears. There are some very fine and complex hand prints east of King’s Canyon in the Northern Territory, pressing three coaxial U shapes to the rock by painting the two inner, the two outer fingers, and the palm.

Paintings can be highly detailed within an individual figure but rarely narrative panels extend across a whole site or rock panel. More typically pre-existing paintings are painted over with no regard for their meaning or author.

There are examples of important images that have been faithfully reproduced because of their fundamental meaning for a given site. It is important to underline this fact, that repainting, when considered over several hundred years is not commonly faithful reproduction but an accumulation of new expression.

Photographs of Mutitjulu waterhole at Uluru, taken by Australian anthropologist Charles Mountford in the late 1930s, are almost unrecognisable due to the accumulated new painting since that time.

Regular painting at Uluru ceased in the 1960s with only a few isolated cases of painting through to the 1980s.

Pigments

In Australia, pigments were chosen from naturally occurring minerals with little evidence of manufacture. Charcoal is one exception to this, but it could be argued that it was a routine by-product rather than a deliberately manufactured pigment.

There is some unsubstantiated speculation that yellow ochre was heated to turn it red and cases where European pigments were adopted. This availability of new colours did not result in the adoption of more colourful paintings, with the exception of some use of washing blue (a coarse synthetic ultramarine) in parts of Arnhem Land.

The traditional palette, that is to say the most commonly encountered colours, are red, white, yellow and black, with variations on the composition of these but with little evidence of mixing to create intermediate tones.

By studying the trace elemental composition of pigments it is possible to connect them to geological events, and hence their source. Such studies proves that pigments were traded, in some cases over long distances. It is difficult to postulate however that distance of manuportation equals significance or spiritual value, but further research may enlighten this fact.

Kaolin – a soft white clay – is abundant in most parts of Australia but where calcite is found, as it is in the river beds of Arnhem Land, it becomes the more common white pigment. The Kimberly is more abundant in the carbonate mineral huntite and yet it is rare to find huntite used outside this region, despite it being a brighter white than kaolin.

Examples of trade exist and some of these provide interesting insights into the selection of paints.

Just south of Uluru, near the South Australian border, lie a group of sites containing a metallic red pigment characteristic of the Walgi Mia quarry 1,000km to the west. It is said these caves and their paintings were created by the emu creation beings who had a dreaming path extending out to the western coastline and which would have passed very nearby the pigment source. It is not surprising therefore to find a pigment that has come from such a distance.

What is fascinating is that near to Walgi Mia is a very large painting site, Walghanna, that features a very large emu footprint. Emus are not known to have existed in the vicinity of Walghanna, according to the archaeological record and oral history. There appears to have been a two-way trade in materials and stories.

Durability and age

The 1930s photograph by Mountford, showing paintings that no longer exist due to subsequent overpainting indicates, among other things, that all of what one sees at Mutitjulu today is “modern art” painted in the period 1936-1962.

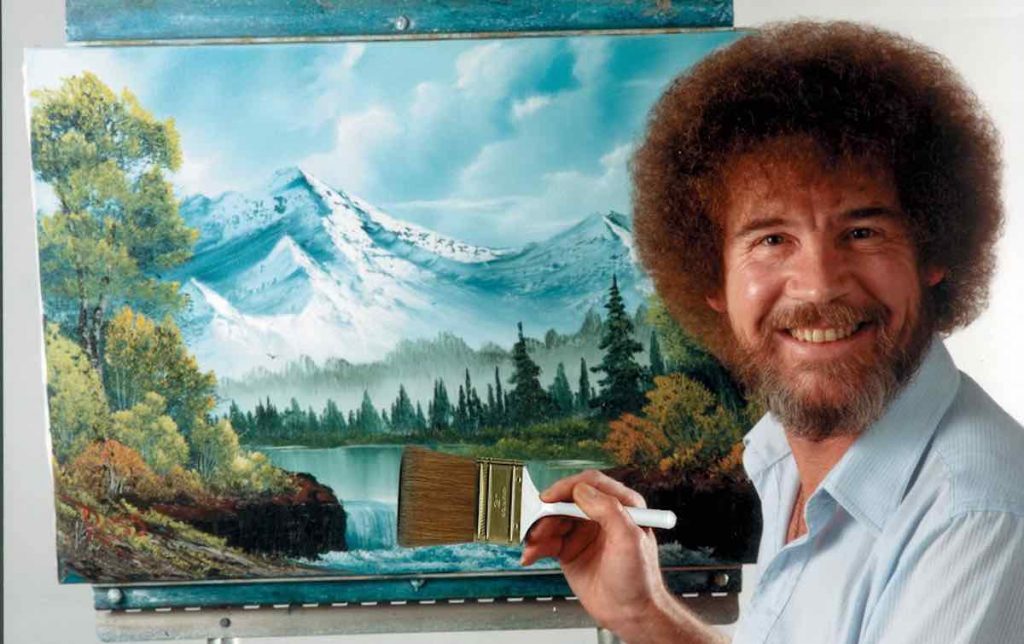

I had great fun at a conference using Powerpoint to fade between an image of the Mutitjulu panel and Convergence, a Jackson Pollock painting with an almost identical scramble of lines, shapes and colours, aimed to make the point that not all rock art is ancient. Some other more significant statements can be added. Most very old paintings survive as very thin remnants.

There are cases in Kakadu of whole colours falling off an image, resulting in, for example, birds without legs. Some very old paintings have survived for thousands of years with every detail seemingly intact, such as those of the dynamic style and others of that period.

These paintings tend to be monochromatic red, applied with haematite that is both very fine and non-responsive to humidity or chemical alteration.

Studies have shown degradation pathways for rock art pigments and it is no surprise that charcoal will jump off the rock very quickly, followed by kaolinite, huntite, then yellow and red ochres.

Dark red haematite is usually the last surviving pigment, unless a painting is subject to floodwaters or other physical agents. There are examples of red paintings surviving under water at Jowalbinna near Laura and east of Mt Isa, both in northern Queensland.

Pigments survive depending on their stability to climatic variations and then ultimately due to their ability to intimately bond with the rock.

It has to be stated that the greatest threat to indigenous rock paintings is the tourist, who out of curiosity rather than malice, desires a sensory connection to inanimate culture.

Having on many occasions adopted the disguise of the tourist I have observed a bus load of fascinated fellow travellers comparing their own hand with that sprayed on the ceiling of Mulga’s Cave just north of Wave Rock.

This is an act of connection with someone from the past but its very execution ensures that connection will soon be lost.

See also:

Stories from the sky: astronomy in Indigenous knowledge

Indigenous medicine – a fusion of ritual and remedy![]()

Andrew Thorn, Heritage Consultant and Materials Conservator; Sessional Lecturer in Stone Conservation, International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recology Recycling Center, where ‘junk’ is being dropped off, and Artists-in-Residence may scavenge

Recology Recycling Center, where ‘junk’ is being dropped off, and Artists-in-Residence may scavenge Recology Artist In Residence Neil Mendoza scavenging through trash with shopping cart

Recology Artist In Residence Neil Mendoza scavenging through trash with shopping cart ‘Mother Spool’ by Nimah Gobir (Photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia for Recology) and ‘Impala’ by Nemo Gould

‘Mother Spool’ by Nimah Gobir (Photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia for Recology) and ‘Impala’ by Nemo Gould Adorned Saw by Eleanor Scholz uses embroidery thread, ribbon, jewelry, keys, bubble wrap, mylar, plastic, and DVDs – Photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia for Recology

Adorned Saw by Eleanor Scholz uses embroidery thread, ribbon, jewelry, keys, bubble wrap, mylar, plastic, and DVDs – Photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia for Recology Knots of Reflection by Nasim Moghadam (mirror, archival pigment print, and Iranian female hair) Photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia

Knots of Reflection by Nasim Moghadam (mirror, archival pigment print, and Iranian female hair) Photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia Out of Africa from the Infinite Jouvay series. -

Out of Africa from the Infinite Jouvay series. -

Guardian Angel of the Refugees -

Guardian Angel of the Refugees - The Beginning of the Maroon Republic -

The Beginning of the Maroon Republic -