Gabriel Golden family at Vanderbilt NICU-SWNS

Gabriel Golden family at Vanderbilt NICU-SWNS

Gabriel Golden family at Vanderbilt NICU-SWNS

Gabriel Golden family at Vanderbilt NICU-SWNS

– credit Leighann Blackwood

– credit Leighann BlackwoodFamilies with young children are yet again reeling after this week’s Four Corners investigation into abuse in the early childhood sector.

The program identified almost 150 childcare workers who had been convicted, charged, or accused of sexual abuse and inappropriate conduct.

System-wide changes are needed to improve standards and safety in the early childhood sector. But parents may also be wondering what they can do in the home to teach their kids about body safety.

There is increasing awareness of how to talk to children about body safety. This includes teaching kids that adults should not ask them to keep secrets and to tell a trusted adult if something feels wrong.

But what about babies and younger children who have not yet learned to talk?

According to Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, children under two can understand language and even communicate before they develop speech. It is never too early to teach them about body autonomy, normalise safety, and model trustworthiness in relationships.

How can parents and caregivers do this?

When you’re talking to a child about their body, you may want to use “baby talk”.

But it is important to use the correct anatomical words for their genitals, the same way that we teach them about other parts of the body.

This reduces shame and normalises body boundaries. It also ensures children grow up being able to describe any experiences clearly if there is a problem.

We teach older children that people should not touch their penis, vagina, or bottom.

But obviously for younger children, parents and carers need to touch their genital areas at nappy changes.

When changing a nappy, you can talk to little children in straightforward language and narrate what you’re doing in simple and easy steps. This is so they understand what a “normal” nappy change looks like.

For example,

I’m going to pick you up now. We need to change your nappy. We change your nappy when it’s dirty. First, I’m going to get a new nappy out of the drawer. Now I’m going to take off your pants. Remember, we only touch your bottom when we need to clean it.

You can normalise consent around touching from the beginning.

For example, teach consent around tickling. Practice using language that invites them to respond: “Would you like to go to Tickletown? Would you like me to tickle you?”

Then teach and demonstrate “yes/no” or “happy/sad” with a smile/frown, or thumbs up/thumbs down.

As they get older this can develop into having a safe word or modelling safe touch and unsafe touch.

Even very young children can send clear messages when they don’t want to be touched or held.

Where possible, respect their “push-away” body language such as pushing back, turning away, wriggling to get down, or arching their back. This teaches them they have autonomy of their bodies.

You can say things like: “Do you want to be put down? Your body belongs to you”.

Family and friends may be eager to hug or kiss your child, especially if they don’t see them often.

Resist the temptation to force your child to hug or kiss adults (“go on, give Grandad a kiss”) – even if it is a special occasion or visit. This teaches children about body boundaries and lets them know they can make decisions about their own bodies

The “my body, my rules” message can be complicated when a child does not want a bath or when they don’t feel like having their nappy changed.

If you meet resistance during these times, calmly explain and narrate what you are doing and why. It will help form a foundation for them to understand healthy and necessary touching and recognise if someone is touching them inappropriately.

For example,

we need to have a bath to wash off all the dirt from the park. Let’s put some soap on your feet where they went in the sandpit.

Preverbal children communicate through gestures and behaviour. Parents can learn to recognise nonverbal cues that might indicate signs of general distress.

In preverbal children such signs might include increased meltdowns or tantrums, withdrawal, unexplained genital pain or redness, changes in appetite, regression in toileting or sleeping, sudden fear or dislike of people or places, and even sudden mood changes or changes in personality.

Learning these signs can improve parent-child interactions and make it easier to recognise early signs of abuse.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, you can call 1800 Respect on 1800 737 732, Lifeline on 131 114, Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800, or Bravehearts (counselling and support for survivors of child sexual abuse) on 1800 272.![]()

Danielle Arlanda Harris, Associate Professor in Criminology and Criminal Justice, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Blueberries on the shrub – SWNS

Blueberries on the shrub – SWNS

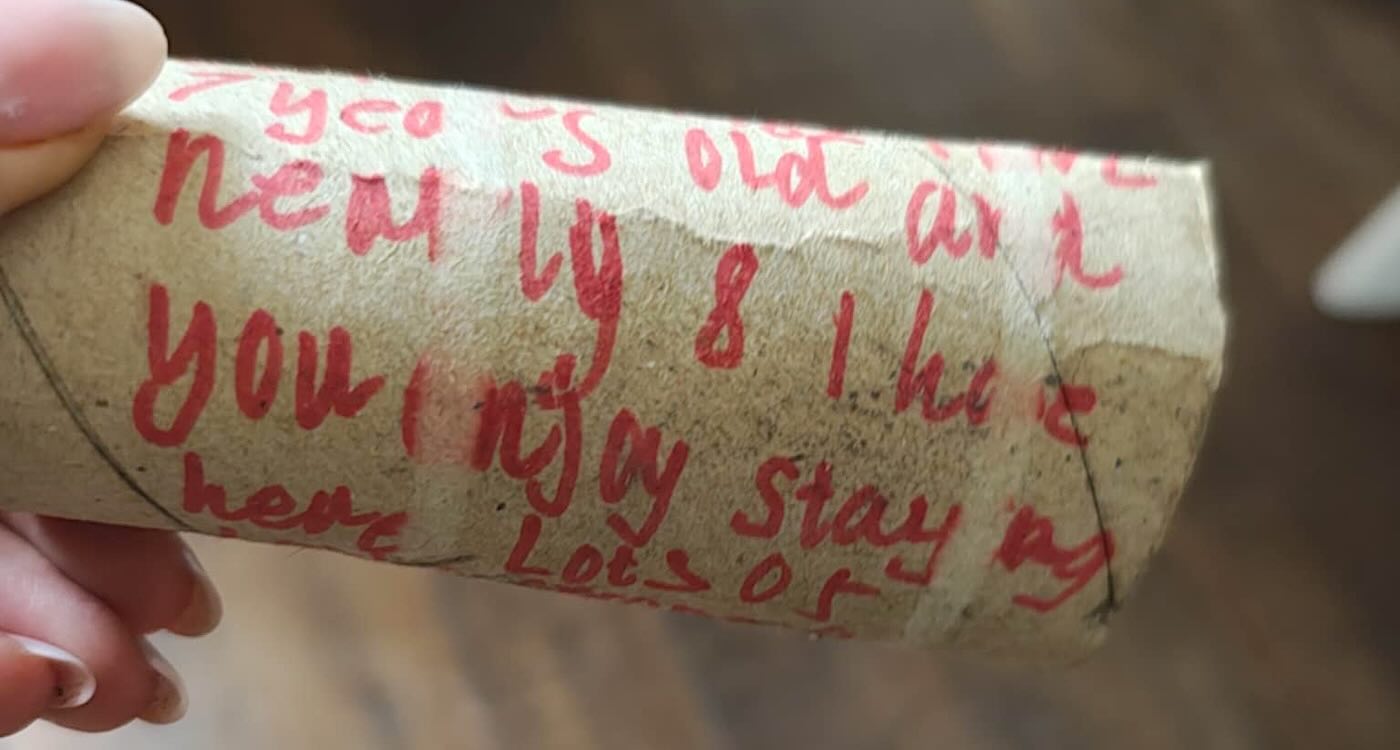

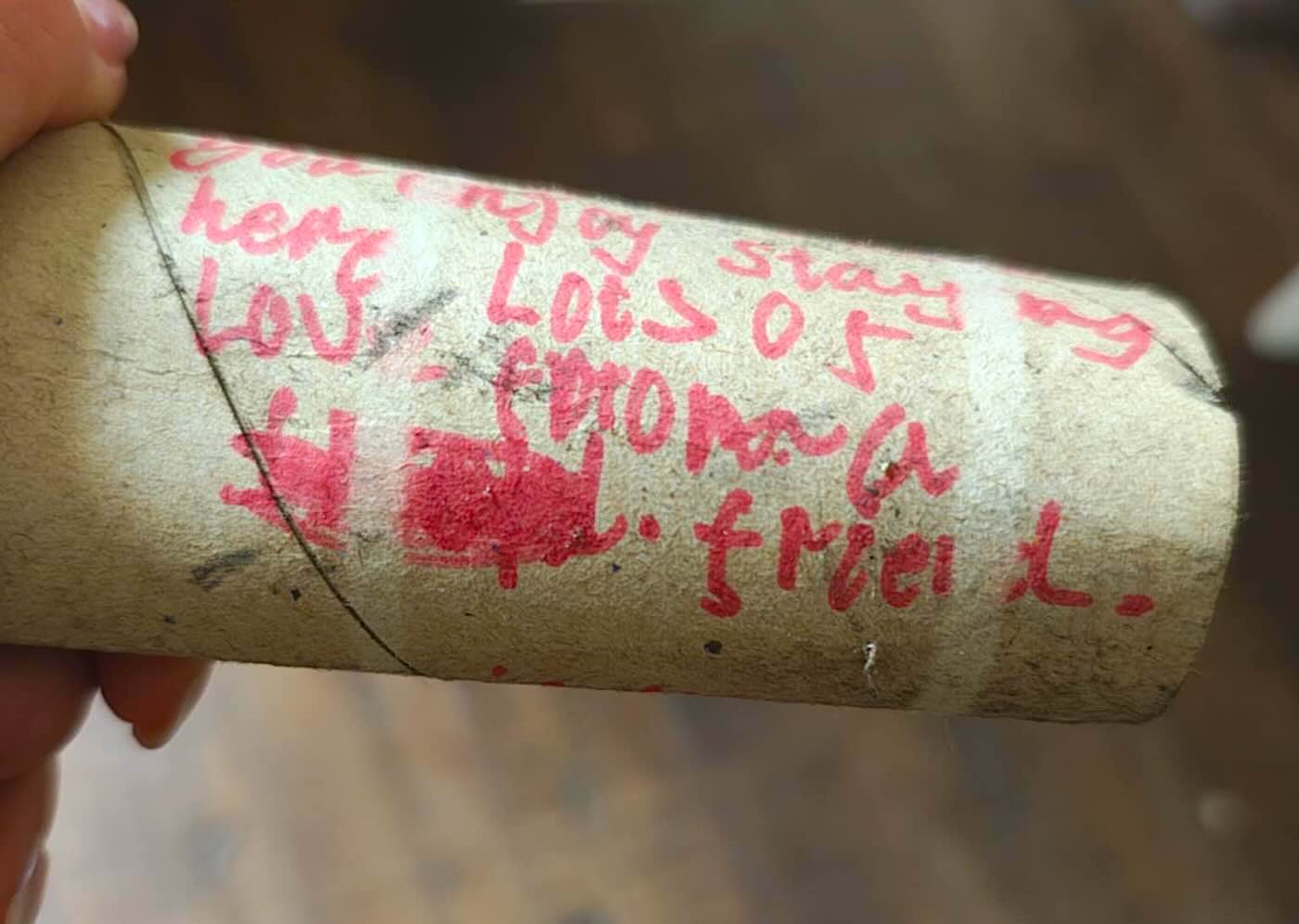

Message on 35-year-old toilet paper roll –Charlotte England-Black / SWNS

Message on 35-year-old toilet paper roll –Charlotte England-Black / SWNS Message on toilet paper roll left by girl 35 years ago –Charlotte England-Black / SWNS

Message on toilet paper roll left by girl 35 years ago –Charlotte England-Black / SWNS Getty Images for Unsplash+

Getty Images for Unsplash+

Photo by Some Tale on Unsplash

Photo by Some Tale on Unsplash

– credit: Quinn Dombrowski, CC 2.0. via Flickr.

– credit: Quinn Dombrowski, CC 2.0. via Flickr. Getty Images / Unsplash+

Getty Images / Unsplash+What we think of as “normal” body shape is affected by what we’re accustomed to – the range of body shapes we see. My new research with colleagues shows that this is true for young children as well as adults.

Research with adults and with children as young as five has already found that our understanding of what a face looks like is always being updated based on the faces we see around us, from childhood through adulthood.

This process of the brain flexibly changing in response to new repeated inputs is known as “adaptation”. When the brain adapts to the same input repeatedly, we can see long term changes in perceptions. For instance, viewing a series of images with larger (as opposed to contracted) facial features leads to an increased preference for large features afterwards.

But so far, research like this on how we view bodies has almost entirely been run with adults.

Among adults, we can see the same effects with body weight that we see with face shape in adults and children. If we are shown a lot of heavy bodies, the bodies we rate as attractive get heavier, the bodies we rate as “normal” get heavier, and the point at which we perceive a body being heavy or not shifts lower. And the opposite happens when we view a lot of thin bodies.

Our study tested whether this also holds true for children. Children aged seven to 15 years of age and adult undergraduate students completed the same experimental study. They rated a series of bodies for how heavy they were, then viewed either 20 very thin figures or 20 very heavy figures, and then rated the same bodies for heaviness as they did at the start.

We found that children, adolescents and adults all rated the same bodies as significantly lighter after viewing the heavy bodies than they did beforehand. This suggests our participants’ mental picture of a “normal” body got heavier, and so every body was perceived as “lighter” than it had been in comparison.

In contrast, those who viewed lighter bodies did not show this shift. They continued to rate the bodies as just as heavy or light as they had beforehand.

It’s difficult to say for sure why this is, although it is likely in part due to the stimuli used. In my own wider research with adults using the same images, I’ve found that larger images tend to produce stronger effects than thin images, but experiments in other labs with adults using different stimuli have shown shifts in perception as a result of viewing both heavier and thinner bodies.

When we compared just the youngest children with the adult participants, we found that the effect of viewing heavy versus light bodies was equally strong in the seven-year-olds as it was in adult students.

These results tell us that the brain’s “model” of a body becomes flexible in the same was as in adults by seven years of age.

Previous research shows that playing with ultra-thin dolls changes young girls’ perceptions of the body they want to have, making them want it to be thinner.

Our new study shows that the effect of dolls on girls’ body ideals isn’t just driven by dolls being aspirational or pretty. Just visual exposure to bodies can change body perceptions. And that means that changing that visual experience, for instance by giving girls a broad range of body sizes and toys, is an important part of maintaining healthy body perceptions.

These results also mean that the large body of research on the effects of visual media on adults’ body perceptions is also likely apply to children as young as seven. For instance, gaining access to television is associated with preferences for thinner bodies in rural communities, and viewing images of muscular male models increases preferences for muscle in male laboratory participants.

Therefore, all of the warnings and recommendations that exist in relation to reducing the biases in the bodies we see in adult’s visual media also apply to children.

Young children in western countries have been shown to associate being heavier with being less pretty or less desirable as a friend. We therefore need to think about how body sizes are represented in all aspects of children’s media and ensure that children do not have a bias towards one size or another if we don’t want them to develop the strong thin ideals that we often see in adulthood.![]()

Lynda Boothroyd, Professor in Psychology, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Credit: AIP via SWNS

Credit: AIP via SWNSLast year, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) issued at least nine recall notices on products that didn’t comply with the mandatory standard for nightwear for children. All of these items posed a fire hazard, but didn’t have the required labelling.

The latest of these recalls, a glow-in-the-dark jumper sold on the website Temu, caused severe burn injuries to an 8-year-old Queensland girl. The incident has exposed significant gaps in Australian product safety standards.

Brands will use warning labels to meet legal requirements (such as the mandatory standard mentioned above), but they continue producing and selling these dangerously flammable textiles. This shifts the responsibility to shoppers who purchase items with fire warning labels, but may not fully understand the implications of the warning.

Highly flammable fabrics are far more common than you might realise – and it’s not just synthetic ones that can easily catch flame.

Textiles are lightweight materials, often with a high surface area meaning they ignite and burn easily. The next time you light a candle, just look at the wick – it’s usually a cotton yarn.

The only naturally flame-resistant fibre is wool, along with all other animal protein fibres such as silk, alpaca, mohair, cashmere and others. These fibres are slow to ignite and form ash when burned.

Synthetic materials melt when burning. If they stick to the skin, they can cause severe injuries that are difficult to treat. Polyester made up over 57% of global fibre production in 2023.

Acrylic is the most flammable of all synthetics. Acrylic fibres are commonly used to make jumpers that look and feel like wool, but are much less expensive to produce. Without checking the label, shoppers can easily mistake acrylic sweaters for wool ones.

Not all synthetic fibres are equally flammable. Somewhat confusingly, there is a flame-resistant fibre called modacrylic. Modacrylic was developed to address the flammability problems with acrylic. Other flame-resistant human-made fibres are kevlar and glass.

However, there is more to fabric flammability than just the fibres alone. Textile fabrics are complex materials – a fabric’s flammability is affected by the fibres, yarns, structure (knit or weave), and any finishes used.

For example, smooth, tightly woven or knitted fabrics will be slower to burn than lightweight or fuzzy fabrics. Fabrics can also be treated with flame retardant finishes.

Fabrics with the highest fire risk are those with a pile or brushed surface (think cosy, fuzzy or furry fleeces, flannelettes and faux furs) and are composed of cotton, acrylic, polyester and other synthetic fibres. These soft and fuzzy (and highly flammable) textile products are everywhere, and often at affordable prices.

Despite well-known fire risks of different materials, Australian rules for fibre content labelling lapsed in 2019. Now, products only legally need care instructions.

Most brands still list the fibre content (for example, “100% cotton”) to meet American and European requirements, but it’s no longer legally required here.

Current safety rules focus mainly on protecting children, particularly in sleepwear and some daily clothes. However, risk from flammable clothing extends beyond children. Women, older people and any person who tends to wear loose-fitting garments that can catch fire more easily are at risk.

Many costume pieces like capes, hoods, wings and tutus are also excluded from children’s product safety rules in Australia. The exclusion of these types of items from regulation is especially baffling, as they often pose a high flammability risk due to their combination of materials and loose-fitting designs.

All this means shoppers may not know the item they are purchasing is highly flammable.

Consider a shopper who encounters flannel fabrics printed with bunnies and dogs at a major Australian retailer. These fabrics come with mandatory warnings like “not intended for children’s sleepwear” or “fire warning: flannelette is a flammable material and care should be taken if using flannelette for children’s sleepwear and loose-fitting garments”.

What are these cutesy flannel fabrics to be used for, if not children’s products?

While Australia has consumer protection laws, the ACCC has acknowledged there is no direct ban on selling unsafe products.

Without stronger legislation prohibiting the production and sale of highly flammable textiles, Australia risks becoming a market for hazardous clothing and textile products that don’t meet stricter international standards.

At the very minimum, Australia needs to reintroduce mandatory fibre content labelling for textiles and clothing products to be in line with US and EU requirements.

In the meantime, consumers need to take action in other ways. Take any product with a “fire warning” label seriously – don’t let children wear fuzzy, fleecy, furry or loose clothing items such as costumes around open flames or as sleepwear. Older adults can also be at risk. Wearing a favourite fuzzy bathrobe when cooking over open flames, such as a gas stove top, is extremely dangerous.

Better yet, don’t purchase any items with a “fire warning” label – brands will stop producing items that don’t sell.

Consumers are encouraged to report any products they suspect are unsafe to the ACCC.![]()

Rebecca Van Amber, Senior Lecturer in Fashion & Textiles, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.