Fun ways to make your grandparents feel special

Two People from Minnesota Who Met in the Hospital After Waking up from Comas Are Getting Married

Zach Zarembinski and Isabelle Richards – credit, family photo

Zach Zarembinski and Isabelle Richards – credit, family photo credit – family photo

credit – family photo Zach and Isabelle after they’d both woken up – credit family photo

Zach and Isabelle after they’d both woken up – credit family photoHope Is the Most Impactful Emotion in Determining Long-Term Economic, Social Outcomes

Parents Reveal the Pros (and Cons) of Having Adult Kids Still Living at Home

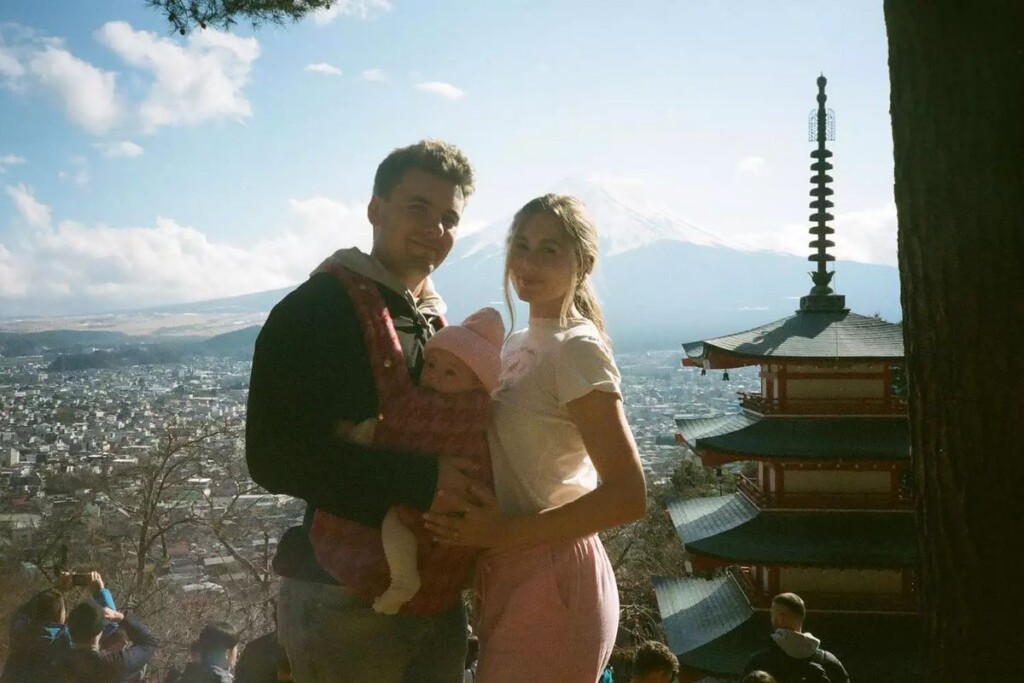

Japanese Woman Offers to Hold New Mother’s Baby so Exhausted Travelers Can Finish Their Meal

credit – Maggie Boynton, retrieved from TikTok

credit – Maggie Boynton, retrieved from TikTok Maggie Boynton and her husband with their daughter in front of Mount Fuji – credit Maggie Boynton, retrieved from TikTok

Maggie Boynton and her husband with their daughter in front of Mount Fuji – credit Maggie Boynton, retrieved from TikTokWatching Sports Boosts Well-being and Improves Your Health, According to ‘Ground-breaking’ Research

Being Social–Like Dining Out, Traveling, or Playing Bingo, May Delay Dementia by 5 Years

Fashion Student Makes ‘Memory Bears’ for Grieving Folks From the Clothing Of Their Deceased Loved Ones

Photo by Mary Macinnes

Photo by Mary Macinnes Photo by Mary Macinnes

Photo by Mary Macinnes Photo by Mary Macinnes

Photo by Mary MacinnesParents Should Sing More to Their Babies For the Positive Impact on Infant’s Mood–And Their Own

Getty Images for Unsplash+

Getty Images for Unsplash+Women Reunited With Sister After DNA Test and 57-year Search Ends the Mystery of a Forced Adoption

Geraldine visiting Mary’s grave for first time – SWNS

Geraldine visiting Mary’s grave for first time – SWNS6 Expert Parenting Tips for Getting Closer to Your Kids–Try Changing Up These Routines

Photo by Some Tale on Unsplash

Photo by Some Tale on Unsplash

– credit: Quinn Dombrowski, CC 2.0. via Flickr.

– credit: Quinn Dombrowski, CC 2.0. via Flickr. Getty Images / Unsplash+

Getty Images / Unsplash+Your fuzzy flannel pyjamas could be incredibly flammable – here’s what to know

Last year, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) issued at least nine recall notices on products that didn’t comply with the mandatory standard for nightwear for children. All of these items posed a fire hazard, but didn’t have the required labelling.

The latest of these recalls, a glow-in-the-dark jumper sold on the website Temu, caused severe burn injuries to an 8-year-old Queensland girl. The incident has exposed significant gaps in Australian product safety standards.

Brands will use warning labels to meet legal requirements (such as the mandatory standard mentioned above), but they continue producing and selling these dangerously flammable textiles. This shifts the responsibility to shoppers who purchase items with fire warning labels, but may not fully understand the implications of the warning.

Highly flammable fabrics are far more common than you might realise – and it’s not just synthetic ones that can easily catch flame.

What makes a fabric flammable?

Textiles are lightweight materials, often with a high surface area meaning they ignite and burn easily. The next time you light a candle, just look at the wick – it’s usually a cotton yarn.

The only naturally flame-resistant fibre is wool, along with all other animal protein fibres such as silk, alpaca, mohair, cashmere and others. These fibres are slow to ignite and form ash when burned.

Synthetic materials melt when burning. If they stick to the skin, they can cause severe injuries that are difficult to treat. Polyester made up over 57% of global fibre production in 2023.

Acrylic is the most flammable of all synthetics. Acrylic fibres are commonly used to make jumpers that look and feel like wool, but are much less expensive to produce. Without checking the label, shoppers can easily mistake acrylic sweaters for wool ones.

Not all synthetic fibres are equally flammable. Somewhat confusingly, there is a flame-resistant fibre called modacrylic. Modacrylic was developed to address the flammability problems with acrylic. Other flame-resistant human-made fibres are kevlar and glass.

However, there is more to fabric flammability than just the fibres alone. Textile fabrics are complex materials – a fabric’s flammability is affected by the fibres, yarns, structure (knit or weave), and any finishes used.

For example, smooth, tightly woven or knitted fabrics will be slower to burn than lightweight or fuzzy fabrics. Fabrics can also be treated with flame retardant finishes.

Fabrics with the highest fire risk are those with a pile or brushed surface (think cosy, fuzzy or furry fleeces, flannelettes and faux furs) and are composed of cotton, acrylic, polyester and other synthetic fibres. These soft and fuzzy (and highly flammable) textile products are everywhere, and often at affordable prices.

‘Not intended for children’s sleepwear’

Despite well-known fire risks of different materials, Australian rules for fibre content labelling lapsed in 2019. Now, products only legally need care instructions.

Most brands still list the fibre content (for example, “100% cotton”) to meet American and European requirements, but it’s no longer legally required here.

Current safety rules focus mainly on protecting children, particularly in sleepwear and some daily clothes. However, risk from flammable clothing extends beyond children. Women, older people and any person who tends to wear loose-fitting garments that can catch fire more easily are at risk.

Many costume pieces like capes, hoods, wings and tutus are also excluded from children’s product safety rules in Australia. The exclusion of these types of items from regulation is especially baffling, as they often pose a high flammability risk due to their combination of materials and loose-fitting designs.

All this means shoppers may not know the item they are purchasing is highly flammable.

Consider a shopper who encounters flannel fabrics printed with bunnies and dogs at a major Australian retailer. These fabrics come with mandatory warnings like “not intended for children’s sleepwear” or “fire warning: flannelette is a flammable material and care should be taken if using flannelette for children’s sleepwear and loose-fitting garments”.

What are these cutesy flannel fabrics to be used for, if not children’s products?

While Australia has consumer protection laws, the ACCC has acknowledged there is no direct ban on selling unsafe products.

Without stronger legislation prohibiting the production and sale of highly flammable textiles, Australia risks becoming a market for hazardous clothing and textile products that don’t meet stricter international standards.

At the very minimum, Australia needs to reintroduce mandatory fibre content labelling for textiles and clothing products to be in line with US and EU requirements.

In the meantime, consumers need to take action in other ways. Take any product with a “fire warning” label seriously – don’t let children wear fuzzy, fleecy, furry or loose clothing items such as costumes around open flames or as sleepwear. Older adults can also be at risk. Wearing a favourite fuzzy bathrobe when cooking over open flames, such as a gas stove top, is extremely dangerous.

Better yet, don’t purchase any items with a “fire warning” label – brands will stop producing items that don’t sell.

Consumers are encouraged to report any products they suspect are unsafe to the ACCC.![]()

Rebecca Van Amber, Senior Lecturer in Fashion & Textiles, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Planning kids? You should know the major parties’ parental leave policies before you vote

Most new Australian mothers receive government paid parental leave to support health, encourage workforce participation and balance work and family life equally with their partners. Despite this, Australia still has one of the least generous parental leave schemes in the developed world.

Both major parties propose to improve the paid parental leave scheme this election.

If you plan on having children, it’s worthwhile understanding what each party promises. Their policies may impact your health, income and the opportunity to pursue your career differently.

What are the major parties promising?

The Australian government provides working parents with paid leave at the minimum wage for up to 18 weeks. This scheme was introduced by Labor in 2011 and represented a “giant leap” in social policy, but it came quite late by OECD standards.

It has since been adjusted to provide partners with two weeks of leave and increase leave-taking flexibility.

This election, the Coalition promises to “enhance” the scheme, although it will keep the total leave amount shared between parents unchanged at 20 weeks. It will also leave payments fixed at the minimum wage.

Instead, the Coalition will allow parents to completely share this leave flexibly between them as they choose, with no separate amounts earmarked for mothers or “dads and partners”.

The Coalition will fix a design flaw in the income test by connecting scheme eligibility to household income, rather than individual income. It will also increase the income threshold that cuts off access at $350,000, allowing 2,200 more families to access the scheme.

Labor has a more generous plan, although they have not set an implementation date and have walked back making their policy a campaign promise. Its eventual goal is to increase total leave from 20 to 26 weeks to be shared between parents. It also seeks to pay benefits at a person’s full salary.

Labor aims to fund their proposed scheme from employer and government contributions. But their plan is scant on details, including how much this policy would cost, what proportion would be funded by business and government, and whether each parent will have leave earmarked for them.

A group that would be better off under either plan is single parents. They would be able to access more leave than the current 18 weeks available to them (Labor’s plan increases leave and the Coalition’s collapses leave for partners into the total leave entitlement).

Leave-taking, gender equality and scheme fairness

Take-up of the current scheme is low among Australian fathers. Some economists have criticised the Coalition’s proposal to remove leave earmarked for fathers and partners, saying it would discourage them from taking any leave at all.

The argument is that if households want to maximise their income, lower paid parents (on average, mothers) would be the ones taking the entire 20 weeks’ leave, since it will be paid at the minimum wage. This means the Coalition’s plan may work against “promoting equality between men and women” in work and family life, despite offering more flexibility.

Labor’s plan better promotes equal leave-taking, since it will pay either parent taking leave their full salary.

Parental leave schemes in other countries offering higher salary replacement are funded by a combination of government, employer and employee contributions.

The Australian scheme already works together with employer-paid leave as 60% of Australian employers also offer paid leave.

This arrangement creates differences in leave-taking between parents who can also use employer-paid leave and those without this privilege. This is inequitable and may translate to differences in mothers’ health outcomes.

Labor has not clarified the details of their proposed government/employer-funded approach. More details are needed on how their scheme would interact with existing employer-paid parental leave policies and whether it would help address existing inequities.

Effects on health

Labor’s plan better supports parent and child health (particularly for those without any employer-paid leave). Research has found six months’ leave after birth for mothers is optimal for their mental health, a minimum amount also suggested by the World Health Organisation for promoting breastfeeding and infant health.

Labor will get Australia’s scheme closer to this benchmark.

When fathers take leave, this is associated with better health outcomes for both mothers and fathers. It also supports children’s development.

The Coalition’s plan doesn’t increase leave from the currently low entitlement. It also only allows mothers to take more leave at the expense of fathers (and vice versa), which may compromise health.

Any changes to parental leave need to balance health promotion and gender equality with supporting women’s workforce participation.

Overly short leave increases the risk of women exiting the labour force, while overly long leave (more than one year) can result in women losing valuable skills and weaken workforce attachment. (Although neither party’s plan is anywhere near generous enough to create this issue).

The current scheme includes six weeks’ paid leave that can be used flexibly between parents any time over the first two years after birth, including while working part-time. This feature potentially supports skill retention and employment attachment, and is probably what the Coalition had in mind when proposing complete flexibility in leave-taking.

Future changes needed to support Australian women

Labor’s plan provides a health-promoting boost to leave, while the Coalition’s recognises the value of flexibility in supporting women’s work. Both plans are lacking in execution; Labor’s on details and the Coalition’s on policy design that promotes equality in leave-taking and caring.

Both parties should consider providing longer and equally split leave for each parent with an additional “flexible” component, or rewarding “bonus” leave to parents who share leave more equally.

Australia has one of the most highly educated and skilled working age female workforces in the OECD. Sadly, this still isn’t reflected in women’s workforce participation, with women more likely than men to work part-time, be under-represented in most industries and earn less.

Policy design matters, but broader changes are needed to draw on this “productivity gold”. This includes promoting high-quality flexible work and normalising fathers taking extended leave to care for children.

Update: this piece was amended to update the fact on Thursday 12 May 2022, Labor Leader Anthony Albanese stated the Labor party is no longer taking its 26 week paid parental leave policy to the election (although it remains a stated “goal” within Labor’s national policy platform).![]()

Anam Bilgrami, Research Fellow, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We reviewed 100 studies about little kids and screens. Here are 4 ways to help your child use them well

Sumudu Mallawaarachchi, University of Wollongong and Dylan Cliff, University of Wollongong

Screen time is one of the top worries for Australian parents. In a national February 2021 poll by the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, parents rated it as the number-one health issue facing their children.

Our previous research also shows parents feel guilty about screens, even though they are all around us.

At the same time, guidance on what parents should be doing is confusing. According to the World Health Organization and the Australian government, young children’s screen time should be limited to no more than one hour per day for two- to five-year-olds, while children under two shouldn’t be exposed to screens at all.

But the UK Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has said it is “impossible to give comprehensive national guidance or limits” because the effect of screens depends so much on context and the evidence is uncertain.

This made us wonder what else matters for children’s healthy development beyond “screen time”. So we gathered all available evidence on the context in which children use screens.

Our research

In our new research, published in JAMA Pediatrics, we reviewed 100 studies on the influence of screen use contexts on the cognitive (brain), social and emotional development in children from birth to five years. The screens included TV, computer games, smartphones and tablets.

These studies, published between 1978 and 2023, involved more than 176,000 children and their families from 30 countries. This included the United States, United Kingdom, China, Canada, Japan and Australia.

From this, we distilled four research-based ways parents can help their children use screens in healthy ways.

1. Make screen time together time

The studies we analysed show that if children and caregivers use screens together (also called co-viewing or co-use), it is beneficial for children’s thinking and reasoning skills. It is especially beneficial for their language development, including the number of words children know, their social communication skills, language understanding and processing.

When you watch together you can have conversations about what children are seeing or doing, help them understand the content (for example, “Why did Bluey hide that from Chilli?”) and draw connections to the real world (“How do you think Bingo is feeling right now?”). This can help their language development and learning.

2. Choose age-appropriate content that encourages play

Not all screen time is “bad” but we should consider the content and how it might influence a child’s development and behaviour.

Our research found a link between children watching age-inappropriate content and poor social skills and behaviour.

This highlights the importance of purposeful and high-quality screen experiences for children. Parents might ask themselves, what age or developmental stage is the content designed for and does it promote learning and development (for example, Sesame Street)?

Does it stimulate imaginative play and creativity in the real world (such as Playschool)? Does the content have positive social messages (Bluey)? Does it encourage movement like dancing to music (Ready, Steady, Wiggle)?

Avoiding violent content and content for mature audiences is key, and parents can use trustworthy guides like those from Common Sense Media if they have any doubts.

3. Don’t let screens get in the way of parent-child interactions

Mobile technologies mean children can use screens almost anywhere and anytime. The same is also true for parents.

Sometimes parents’ screens can interfere with conversations and connections between them and their child. In our study, children had better social skills, behaviour and ability to regulate their emotions when parents avoided screen use during interactions and routines like family meals.

When parents are distracted, it can affect the quality and quantity of interactions with their child.

4. Don’t have the TV on in the background

Children learn from their environments and background TV may divert a child’s attention from play and learning. Our research found children had better thinking, reasoning and language abilities when there was less background TV in the home.

This can also be because of less conversations between parents and children when there is a TV on in the background.

So, when the TV is not actively being watched, consider turning it off so children can play, listen and learn.

Jade Burley co-led the research described in this article.![]()

Sumudu Mallawaarachchi, Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child, University of Wollongong and Dylan Cliff, Associate Professor in Health and Physical Education, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Characteristics of growing up in a controlled parenting environment

Parents Reveal Their Top 10 Sneaky Techniques for Getting Kids to Eat Vegetables

It can be quite a struggle for parents to get stubborn children to eat their vegetables—which is why generations of them have come up with creative methods for sneaking nutrition into their kids’ diets.

- 1. Allowing your child to help cook meals so they will be more likely to eat them

- 2. Letting your child pick their own healthy snacks

- 3. Letting your child pick a few meals for the family to have each week

- 4. Only letting your child eat dessert if they’ve finished their vegetables

- 5. Switching the packaging from an unhealthy snack to a healthy snack

- 6. Bribing your child with a treat to get them to finish their dinner

- 7. Letting your child put a little ketchup on things they don’t like, so they will eat them

- 8. Using the “one more bite” rule over and over to get your child to finish their meal

- 9. Buying snacks with characters your child likes on the packaging so they would be more likely to eat it

- 10. Making faces with the food so your child will be entertained and be more likely to eat it.