Image Source: IANS News

Image Source: IANS NewsA true story of love lost & found in WWII

Image Source: IANS News

Image Source: IANS NewsMilind Soman's mother does skipping every day even at 86

9-Year-old Double Amputee Made History on ‘New York Fashion Week’ Catwalk

SWNS

SWNS

Fashion Designers Replace Plastic-Based Vegan ‘Leather’ With Fabric Made Out of Apple Peels

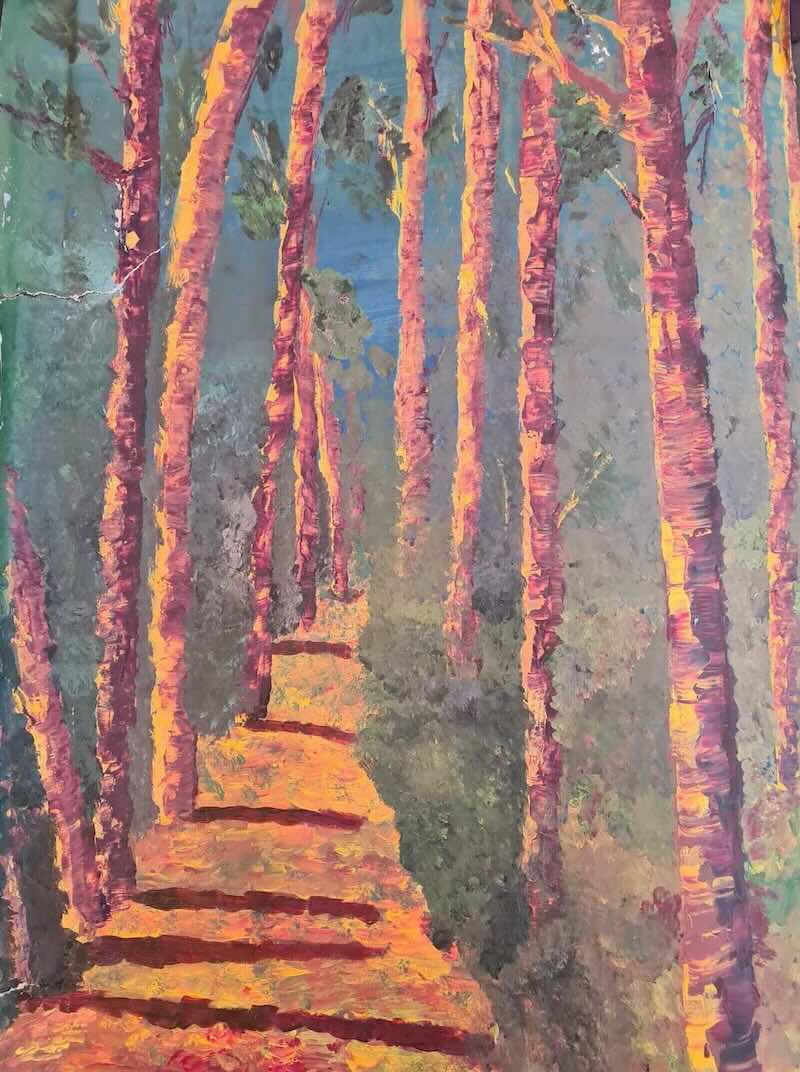

Artist Uses Cremation Ashes to Create Unique Memorial Paintings With Personal Meanings

Artist Gary Harper uses cremation ashes to make personalized paintings for grieving families – SWNS

Artist Gary Harper uses cremation ashes to make personalized paintings for grieving families – SWNS Artist Gary Harper uses cremation ashes to make personalized paintings of landscapes or still life – SWNS

Artist Gary Harper uses cremation ashes to make personalized paintings of landscapes or still life – SWNS

Intermittent fasting doesn’t have an edge for weight loss, but might still work for some

Evelyn Parr, Australian Catholic University

Intermittent fasting has become a buzzword in nutrition circles, with many people looking to it as a way to lose weight or improve their health.

But new research from the Cochrane Collaboration shows intermittent fasting is no more effective for weight loss than receiving traditional dietary advice or even doing nothing at all.

In this international review, researchers assessed 22 studies involving 1,995 adults who were classified as overweight (with a body mass index of 25–29.9 kg/m²) or obese (with a BMI of 30 kg/m² or above) to assess the effectiveness of intermittent fasting for up to 12 months.

The authors found, when compared to energy restricted dieting, intermittent fasting doesn’t seem to work for people who are overweight or obese and are trying to lose weight. However they note intermittent fasting may still be a reasonable option for some people.

Remind me, what’s intermittent fasting?

Intermittent fasting is a tool for weight management, which includes three main strategies:

alternate day fasting, where every second day is reduced to low or no energy intake

periodic fasting or the 5:2 diet, where one or two days of the week are spent with low or no energy intake

time-restricted eating or the 16:8 diet, where daily energy intake is reduced to a shorter window, usually between eight and ten waking hours.

What did previous research show?

Previous reviews have found differences between types of intermittent fasting.

Alternate day fasting, for example, resulted in more weight loss when compared to time-restricted eating.

This is because participants who fasted every second day consumed about 20% less energy than those following time-restricted eating.

What did the Cochrane review find?

Cochrane review use gold-standard techniques to give an objective overview of the evidence. This review looked at 22 individual randomised controlled trials published between 2016 and 2024 from North America, Europe, China, Australia and South America.

The trials compared the outcomes of almost 2,000 adults who were classified as being overweight or obese. These participants either:

received standard dietary advice, such as restricting calories or eating different types of foods

practised intermittent fasting

received either regular dietary advice, no intervention or were on a wait list.

The authors found:

1. Intermittent fasting was no better than getting dietary advice

The researchers found intermittent fasting and receiving dietary advice to restrict energy intake led to similar levels of weight loss.

This finding was based on 21 studies involving 1,713 people, with the researchers measuring the change from the participants’ starting weight.

Dietary advice (from registered dietitians or trained researchers) could include an eating plan focused on fruit, vegetables, whole grains and seafood, restricting calories, or any specific dietary advice for weight loss.

The amount of weight the participants lost ranged from a 10% loss to a 1% gain, with either intermittent fasting or dietary advice.

These findings are similar to several recent meta-analyses which found intermittent fasting is no better than dieting.

Previous research has found most of the alternate day fasting and periodic diet studies leads to about 6% to 7% weight loss. This is compared to very low energy “shake” diets (about 10%), GLP-1 medications (15% to 20%) and surgery (above 20%).

The review also found intermittent fasting likely makes little difference to a person’s quality of life, based on only three studies.

2. Intermittent fasting was no better than doing nothing

The researchers found intermittent fasting and no intervention led to similar levels of weight loss. This finding was based on six studies involving 448 people.

In the intermittent fasting studies, participants experienced about 5% weight loss. The “no intervention” or control group lost about 2% of their original weight.

In research, a 3% difference in weight loss is not considered clinically meaningful. That’s why the authors of this review concluded intermittent fasting is no more effective for weight loss than doing nothing at all.

However, the result for the “no intervention” condition could be due to the Hawthorne effect: the tendency for people to behave differently because they know they are being watched, such as in a clinical trial.

What are the review’s limitations?

There were few large, high-quality randomised controlled trials to draw on.

Only six studies were included in the part of the review which compared intermittent fasting and doing nothing. Two of these focused on time-restricted eating, which is arguably the least effective weight-loss strategy. One looked at the effects of fasting for one day per week. The other three were intermittent fasting studies, each with varying control groups, where some received guidance and others did not.

Also, the review only looked at studies where the interventions lasted between six and 12 months. It’s possible intermittent fasting strategies could be a long-term tool for weight maintenance. So we need to do more research, and ideally studies of longer duration.

What about the other health benefits of fasting?

Studies have found intermittent fasting can lower blood pressure, improve fertility, and reduce the incidence of metabolic syndrome which refers to a group of conditions that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

In one 2024 study, researchers found intermittent fasting may lead to changes in metabolism and the gut that restrict how cancer develops. Another study from 2025 found intermittent fasting could improve the metabolic health of shift workers.

So if you’re practising or considering intermittent fasting, the current evidence suggests it can be a safe and effective way to manage your weight.

But for any weight loss strategy to work, it needs to align with your personal preferences. And it’s best to consult a health-care professional before starting any new diet, especially if you have any underlying health conditions.![]()

Evelyn Parr, Research Fellow in Exercise Metabolism and Nutrition, Mary MacKillop Institute for Health Research, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Runners, flat shoes or bare foot – what should I wear to lift weights?

Hunter Bennett, Adelaide University

If you go to the gym often, you might have been told you shouldn’t lift weights in runners.

The common belief is it is bad for your performance and can lead to injuries.

But is this really the case? Let’s unpack the science.

What your feet are doing when you lift

Your feet are key to exercising safely and effectively.

When you walk and run, they act like a springs and help propel you forward with each step. Your feet also help you maintain balance by supporting your weight.

When you lift any amount of weight (for example, doing compound exercises such as squats) your feet are working hard to keep you stable – even if you’re not thinking much about them.

Researchers have also suggested having a stable foot helps you push more efficiently into the ground. This may increase the amount of weight you can safely lift.

But what you wear on your feet may also contribute to this.

Can’t I just wear runners?

Unsurprisingly, given their name, running shoes are designed specifically to improve your performance and protect your feet while running.

They generally have a raised heel, a thick, cushioned sole to absorb shock, and a “rocker” shape that helps you roll from your heel to your toe. These features help reduce the impact of running on your body.

But in the gym, this cushioned sole may absorb the force you create when lifting weights, making you feel less stable, strong, and powerful. This is likely why some people may say you shouldn’t lift weights in running shoes.

Some people may be concerned this can lead to weightlifting injuries.

One 2016 study found wearing running shoes for exercises like squats can change how your ankle and knee joints move. But there is no peer-reviewed evidence linking these changes to injury.

What are my other options?

Aside from running shoes, there are three other shoe types people generally wear while lifting weights: minimalist (sometimes called “barefoot”), flat or weightlifting shoes.

Minimalist shoes are designed to simulate being barefoot. They have thin soles with almost no cushioning, and aim to let the foot interact with the ground as if you were not wearing shoes at all. Flat sneakers designed for casual wear, such as Vans or Converse, also have thin soles without cushioning.

As a result, these types of shoes may be a good choice for lifting weights because they will be more stable than runners.

In contrast, weightlifting shoes are designed to improve how you perform in the gym.

They typically have a raised heel and a solid, stiff sole without any give, often made of wood or hard plastic. This helps you stay stable at the bottom of a deep squat, which is particuarly useful for movements such as squats, cleans and snatches.

But how do these different shoes stack up?

Studies looking at the impact of footwear on gym performance is largely limited to the squat and deadlift, probably because these are focused on leg strength.

One study from 2020 comparing running and weightlifting shoes found the latter helped people squat with a more upright torso and more flexibility in their knees.

This can take stress off the lower back and make your leg muscles work harder, which is the main purpose of the exercise.

Similarly, research from 2016 showed people wearing weightlifting shoes felt more stable when squatting. This suggests they may be a better option for that specific exercise.

A 2018 study focused on people performing deadlifts. It found running shoes reduced how quickly people could push force into the ground compared to when they wore only socks. This may suggest that they were more stable without running shoes.

However, this difference was small and has not been consistently replicated in other studies.

So what shoes should I wear?

That ultimately depends on your personal goals and situation.

Weightlifting shoes might be your best bet when doing squats. But if you mainly stick to deadlifts, flat shoes may slightly boost your performance. That is if your goal is to lift as much weight as possible.

However, if you are an Olympic weightlifter who needs to get into a deep squat position for competition, weightlifting shoes are the ideal option.

For everyone else, what shoes you wear may not matter as much. So wear whatever is most comfortable and keep lifting those weights.![]()

Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, Adelaide University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Hair care for Summer: Best Home Remedies for Your Hair

- Soak fuller’s earth in water overnight. Add 2 tablespoonful of curd to it to make a paste. Apply this mixture to your scalp and hair. Wash with water after an hour to attain soft, shiny and healthy hair.

- For keeping your hair moisturized and protected from sun rays, combine equal parts of aloe vera gel and olive oil. Apply the mixture gently to the scalp and hair. Leave it for up to 30 minutes and rinse it out.

- Take a ripe papaya and blend it in the mixer. Mix a cup of yogurt to it and apply thoroughly through scalp and hair. Wash after half an hour with water.

- Take equal proportions of powdered Amla, Reetha and Henna and add water to make a paste. Leave this mixture overnight. Next morning, mix 2 tablespoon curd to the paste and apply over scalp and hair. Leave it on for an hour. Rinse hair with a mild shampoo afterwards. This is one of the best conditioner for heat affected hair.

- Take egg yolk in a bowl and whip it well. Add honey and stir it well to make a thick liquid. Apply the mixture onto your scalp and hair and let it sit for up to 30 minutes. This remedy would make your hair soft and bouncy.

- Almond oil can also be used to treat dry and damaged hair. Take some almond oil in a bowl and heat it gently. Massage the lukewarm oil to the scalp and hair. Leave it for 30 minutes and then rinse normally with shampoo.

- Mash a ripe banana and mix a tablespoon of honey to make a paste. This is one of the beneficial remedies to treat sun affected hair.

- Soak fenugreek (methi) seeds overnight and grind the same next morning. Mix a spoonful of curd to make a paste. Massage this paste gently on scalp and hair. Rinse with a mild shampoo after 20-30 minutes.

- The most effective remedy for health hair is eating healthy diet including green vegetables and fresh fruits.

- As hair is made of protein, your diet should include plenty of natural meat, fish, and dairy products.

- Drink plenty of water (3-4 liters/ day) to keep your hair and skin hydrated.

- When you go out in the sun, remember to wear a hat, cap or scarf, slightly loose enough to allow scalp circulation, to protect your hair against the damaging effects of the sun.

- Avoid maximum ray damage by minimizing bare head exposure to the sun between 10 am - 3 pm, when the sun's rays are the strongest.

- Avoid hot water hair wash, as the heat can damage your hair. Use cool water instead.

- Avoid using blow-dryer or hot rollers, instead allow your hair to dry by itself. These artificial techniques make hair brittle and dry. If you have no time to let your hair air dry, then use blow-dryer sparingly and make sure you use a warm setting instead of a hot setting.

- Try using mild and moisturizing shampoo during summer, rather than the normal shampoo that you use during other times, as former is much gentle on your hair.

Best jobs for travel lovers ( list of 10 )

This Ancient Man's Piercing Hazel Eyes Drew Almost $1 Million in 'Mummy Portrait' Auction

Juice cleanses, charcoal supplements and foot patches – is detoxing worth the hype?

Katie Edwards, The Conversation and Dan Baumgardt, University of Bristol

January arrives with a familiar hangover. Too much food. Too much drink. Too much screen time. And suddenly social media is full of green juices, charcoal supplements, foot patches and seven-day “liver resets”, all promising to purge the body of mysterious toxins and return it to a purer state.

In the first episode of Strange Health, a new visualised podcast from The Conversation, hosts Katie Edwards and Dan Baumgardt put detox culture under the microscope and ask a simple question: do we actually need to detox at all?

Strange Health explores the weird, surprising and sometimes alarming things our bodies do. Each episode takes a popular health or wellness trend, viral claim or bodily mystery and examines what the evidence really says, with help from researchers who study this stuff for a living.

Katie Edwards, a health and medicine editor at The Conversation and Dan Baumgardt, a GP and lecturer in health and life sciences at the University of Bristol share a longstanding fascination with the body’s improbabilities and limits, plus a healthy scepticism for claims that sound too good to be true.

This opening episode dives straight into detoxing. From juice cleanses and detox teas to charcoal pills, foot pads and coffee enemas, Katie and Dan watch, wince and occasionally laugh their way through some of the internet’s most popular detox trends. Along the way, they ask what these products claim to remove, how they supposedly work, and why feeling worse is often reframed online as a sign that a detox is “working”.

The episode also features an interview with Trish Lalor, a liver expert from the University of Birmingham, whose message is refreshingly blunt. “Your body is really set up to do it by itself,” she explains. The liver, working alongside the kidneys and gut, already detoxifies the body around the clock. For most healthy people, Lalor says, there is no need for extreme interventions or pricey supplements.

That does not mean everything labelled “detox” is harmless. Lalor explains where certain ingredients can help, where they make little difference and where they can cause real damage if misused.

Real detoxing looks less like a sachet or a foot patch and more like hydration, fibre, rest, moderation and giving your liver time to do the job it already does remarkably well. If you’re buying detox patches and supplements then it’s probably your wallet that is about to be cleansed, not your liver.

Strange Health is hosted by Katie Edwards and Dan Baumgardt. The executive producer is Gemma Ware, with video and sound editing by Sikander Khan. Artwork by Alice Mason.

Dan and Katie talk about two social media clips in this episode, one from 30.forever on TikTok and one from velvelle_store on Instagram.

Listen to Strange Health via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here. A transcript is available via the Apple Podcasts or Spotify apps.![]()

Katie Edwards, Commissioning Editor, Health + Medicine and Host of Strange Health podcast, The Conversation and Dan Baumgardt, Senior Lecturer, School of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

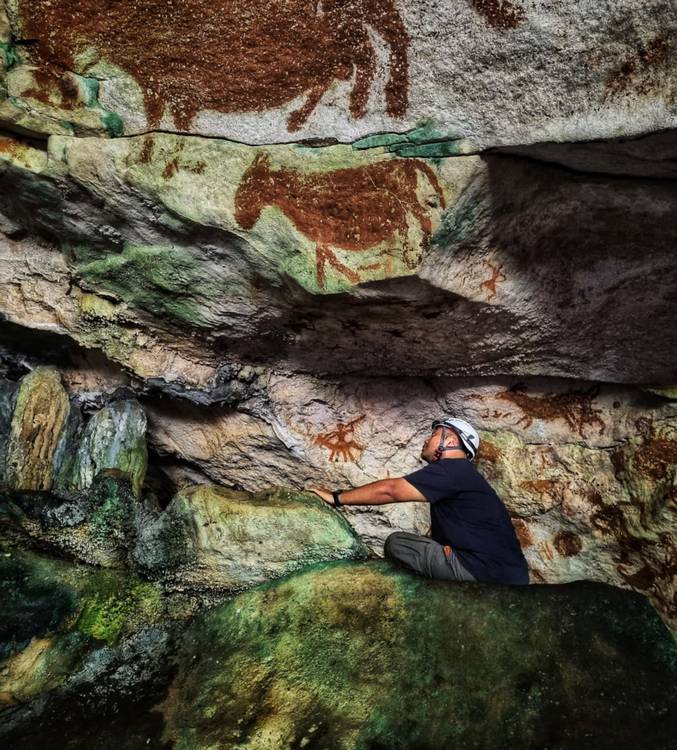

At 67,800-years-old, These Handprints Just Discovered in Indonesia Are Oldest Example of Rock Art

Exercise can be as effective as medication for depression and anxiety – new study

Depression and anxiety affect millions of people worldwide.

While treatments such as medication and psychotherapy (sometimes called talk therapy) can be very effective, they’re not always an option. Barriers include cost, stigma, long waiting lists for appointments, and potential drug side effects.

So what about exercise? Our new research, published today, confirms physical activity can be just as effective for some people as therapy or medication. This is especially true when it’s social and guided by a professional, such as a gym class or running club.

Let’s take a look at the evidence.

What we already knew

Physical activity has long been promoted as a treatment option for anxiety and depression, largely because it helps release “feel good” chemicals in the brain which help boost mood and reduce stress.

But the evidence can be confusing. Hundreds of studies with diverse results make it unclear how much exercise is beneficial, what type, and who it helps most.

Over the past two decades, researchers have conducted dozens of separate meta-analyses (studies that combine results from multiple trials) examining exercise for depression and anxiety. But these have still left gaps in understanding how effective exercise is for different age groups and whether the type of exercise matters.

Many studies have also included participants with confounding factors (influences that can distort research findings) such as other chronic diseases, for example, diabetes or arthritis. This means it can be hard to apply the findings more broadly.

What we did

Our research aimed to resolve this confusion by conducting a “meta-meta-analysis”. This means we systematically reviewed the results of all the existing meta-analyses – there were 81 – to determine what the evidence really shows.

Together, this meant data from nearly 80,000 participants across more than 1,000 original trials.

We examined multiple factors that might explain why their results varied. These included differences in:

who they studied (for example, people with diagnosed depression or anxiety versus those just experiencing symptoms, different age groups, and women during pregnancy and after birth)

what the exercise involved (for example, comparing aerobic fitness to resistance training and mind-body exercises, such as yoga; whether it was supervised by a professional; intensity and duration)

whether the exercise was individual or in a group.

We also used advanced statistical techniques to accurately isolate and estimate the exact impact of exercise, separate from confounding factors (including other chronic diseases).

Our data looked at the impact of exercise alone on depression and anxiety. But sometimes people will also use antidepressants and/or therapy – so further research would be needed to explore the effect of these when combined.

What did the study find?

Exercise is effective at reducing both depression and anxiety. But there is some nuance.

We found exercising had a high impact on depression symptoms, and a medium impact on anxiety, compared to staying inactive.

The benefits were comparable to, and in some cases better than, more widely prescribed mental health treatments, including therapy and antidepressants.

Importantly, we discovered who exercise helped most. Two groups showed the most improvement: adults aged 18 to 30 and women who had recently given birth.

Many women experience barriers to exercising after giving birth, including lack of time, confidence or access to appropriate and affordable activities.

Our findings suggest making it more accessible could be an important strategy to address new mothers’ mental health in this vulnerable time.

How you exercise matters

We also found aerobic activities – such as walking, running, cycling or swimming – were best at reducing both depression and anxiety symptoms.

However, all forms of exercise reduced symptoms, including resistance training (such as lifting weights) and mind-body practices (such as yoga).

For depression, there were greater improvements when people exercised with others and were guided by a professional, such as a group fitness class.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t available data on group or supervised exercise for anxiety, so we would need more research to find out if the impact is similar.

Exercising once or twice a week had a similar effect on depression as exercising more frequently. And there didn’t seem to be a significant difference between exercising vigorously or at a low intensity – all were beneficial.

But for anxiety, the best improvements in anxiety symptoms were when exercise was done:

consistently, for up to eight weeks, and

at a lower intensity, such as walking or swimming laps at a gentle pace.

So, what does all this mean?

Our research shows exercise is a legitimate and evidence-based treatment option for depression and anxiety, particularly for people with diagnosed conditions.

However, simply telling patients to “exercise more” is unlikely to be effective.

The evidence shows structured, supervised exercise with a social component is best for improving depression and anxiety. The social aspect and the accountability may help keep people motivated.

Clinicians should keep this in mind, offering referrals to specific programs – such as aerobic fitness classes or supervised walking and running programs – rather than general advice.

The findings also suggest this kind of exercise can be particularly effective when targeted to depression in younger adults and women who’ve recently given birth.

The takeaway

For people who are hesitant about medication, or facing long waits for therapy, supervised group exercise may be an effective alternative. It’s evidence-based, and you can start any time.

But it’s still best to get advice from a professional. If you have anxiety or depression symptoms, you should talk to your GP or psychologist. They can advise where exercise fits in your treatment plan, potentially alongside therapy and/or medication.![]()

Neil Munro, PhD Candidate in Psychology, James Cook University; James Dimmock, Professor in Psychology, James Cook University; Klaire Somoray, Lecturer in Pyschology, James Cook University, and Samantha Teague, Senior Research Fellow in Psychology, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fun ways to make your grandparents feel special

Personal transformation in 6 simple steps

Oats: The Best Healthy Snacks!

Your sense of self is deeply tied to your memory – here’s how

Shane Rogers, Edith Cowan University

You might say you have a “bad memory” because you don’t remember what cake you had at your last birthday party or the plot of a movie you watched last month. On the other hand, you might precisely recall the surface temperature of the Sun any time when asked.

So, is your memory bad, or just fine? Memory is at the very heart of who we are, but it’s surprisingly complex once we start looking at how it all fits together.

In fact, there’s more than one type of memory, and this determines how we recall certain facts about the world and ourselves.

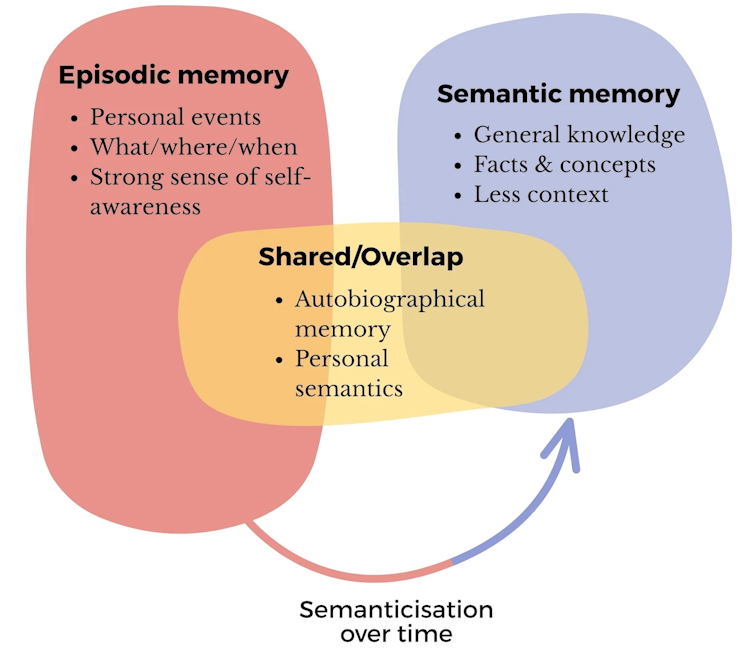

How do we classify memory?

Cognitive psychologists distinguish between declarative memory and non-declarative memory. Non-declarative memories are expressed without conscious recollection, such as skills and habits like typing on a keyboard or riding a bike.

But memories you’re consciously aware of are declarative – you know your name, you know what year it is, and you know there is mustard in the fridge because you put it there.

However, not all of our memories are stored in the same way, nor in the same place in our brains. Declarative memory can be further broken down into semantic memory and episodic memory.

Semantic memory refers to general knowledge about the world. For example, knowing that cats are mammals.

Episodic memory refers to episodes of your life, typically with elements of “what”, “where” and “when”. For example, I remember cuddling my pet cat (what) in my home office (where) just before sitting down to write this article (when).

A sense of self-awareness is strongly involved in episodic memory. It’s the feeling of personally remembering.

For semantic memories, this sense is not as strong – you can have detached knowledge without the context of “how” and “when”. For instance, I know that Canberra is the capital city of Australia (semantic memory), yet I can’t remember specifically when and where I learnt this (episodic memory).

Lessons from amnesia

In the mid-20th century, famous case studies of amnesic patients were the early evidence of this distinction between semantic and episodic memory.

For example, Henry Molaison and Kent Cochrane both experienced brain damage that severely impacted their episodic memory abilities.

They couldn’t recall events from their lives, but knew many things about the world in general. In effect, their personal past had vanished, even though their general knowledge remained intact.

In one interview after the accident that caused his brain damage, Cochrane was able to describe how to change a flat tire in perfect detail – despite not remembering having ever done this task.

There have also been reports of cases of people whose ability to recall semantic memories is largely impaired, while their episodic memory abilities seem mostly fine. This is known as semantic dementia.

Your age affects how your memory works

Young children have both memory systems, but they develop at different rates. The capacity to form strong semantic memories comes first, while episodic memory takes longer.

In fact, true episodic memory ability may not fully develop until around the age of three or four years. This helps explain why you have scant memories of your earliest childhood. We gain greater self-awareness around the same age too.

While episodic memory ability develops more slowly in early life, it also declines more quickly in old age. On average, older adults tend to remember fewer episodic details compared to younger adults in memory recall assessments.

In older adults with more severe cognitive decline, such as dementia, the ability to recall episodic memories is typically much more affected, compared to semantic memories. For example, they might have difficulty remembering they had pasta for lunch the day before (episodic memory), while still having perfect knowledge of what pasta is (semantic memory).

Ultimately, it all works together

Brain imaging studies have actually revealed that overlapping areas of the brain are active when recalling both semantic and episodic types of memories. In a neurological sense, these two types of memory appear to have more similarities than differences.

In fact, some have suggested episodic and semantic memory might be better thought of as a continuum rather than as completely distinct memory systems. These days, researchers acknowledge memory recall in everyday life involves tight interaction between both types.

A major example of how you need both types to work together is autobiographical memory, also called personal semantics. This refers to personally relevant information about yourself.

Let’s say you call yourself “a good swimmer”. At first glance, this may appear to be a semantic memory – a fact without the how, why, or when. However, recall of such a personally relevant fact will likely also produce related recall of episodic experiences when you’ve been swimming.

All this is related to something known as semanticisation – the gradual transformation of episodic memories into semantic memories. As you can imagine, it challenges the distinction between semantic and episodic memory.

Ultimately, how we remember shapes how we understand ourselves. Episodic memory allows us to mentally return to experiences that feel personally lived, while semantic memory provides the stable knowledge that binds those experiences into a coherent life story.

Over time, the boundary between the two softens as specific events are condensed into broader beliefs about who we are, what we value, and what we can do. Memory is not simply a storehouse of the past. It’s an active system that continually reshapes our sense of identity.![]()

Shane Rogers, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.jpg)

.jpg)